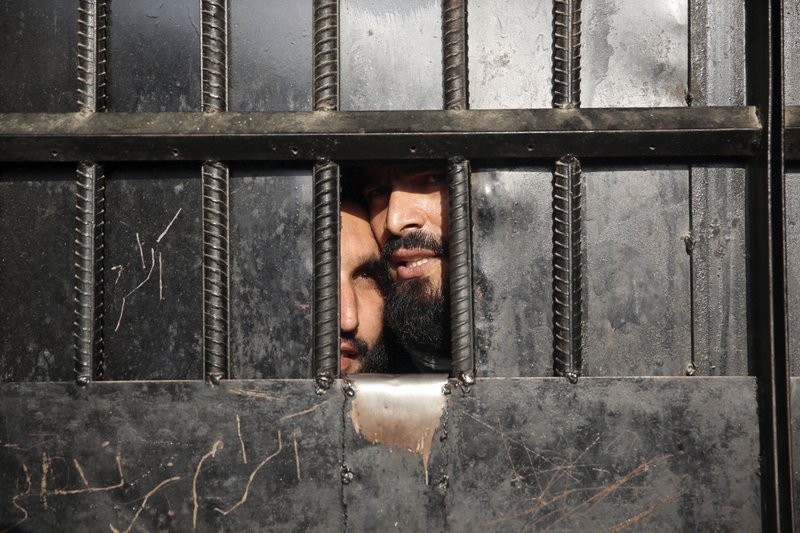

In this Monday, Aug. 3, 2020 file photo, Taliban prisoners watch through the door inside the prison after an attack in the city of Jalalabad, east of Kabul, Afghanistan. Afghanistan has been at war for more than 40 years, first against the invading Soviet army that killed more than 1 million people, then feuding mujahedin groups in a bitter civil war followed by the repressive Taliban rule and finally the latest war that began after the 2001 U.S.-led coalition invasion that toppled the Taliban government. (AP Photo/Rahmat Gul, File)

KABUL, Afghanistan (AP) —

At a Kabul museum honoring Afghanistan’s war victims, talking to visitors reveals just how many layers and generations of pain and grief have piled up during four decades of unrelenting conflict.

Fakhria Hayat recalled an attack that changed her family forever. It was 1995, and the Afghan capital was under siege, pounded by rockets fired by rival mujahedeen groups. Her world exploded: A rocket slammed into her yard, killing her brother and leaving her sister forever in a wheelchair.

Danish Habibi was just a child in 2000 when the Taliban overran his village in Afghanistan’s serene Bamiyan Valley. His memories of those days are reoccurring nightmares. Men were forcibly separated from wives and children. Dozens were killed. Habibi’s father disappeared only to return a beaten, broken man, never able to work again. Habibi wonders how he will be able to accept peace with the Taliban.

Reyhana Hashimi told of how her 15-year-old sister, Atifa, was killed by Afghan security forces. It was 2018. Atifa had left home to take her exams, only to get entangled in a demonstration protesting the arrest of a Hazara leader. Afghan forces opened fire on protesters.

“They shot my sister right in the heart,” Hashimi said. “No one from the government even came to apologize. They tried to say she was a protester. She wasn’t. She just wanted to write her exams.”

Today, those accumulated, unresolved grievances cast a long shadow on the intra-Afghan negotiations underway in the Gulf nation of Qatar.

Washington signed a deal with the Taliban in February to pave the way for the Doha talks and American forces’ eventual withdrawal. The Americans championed the deal as Afghanistan’s best chance at a lasting peace.

Afghans are not so sure. They say preventing the next war is as vital as ending the current one.

Afghanistan has been at war for more than 40 years. First was the Soviet invasion in 1979 and nine years of fighting. The Soviet withdrawal opened a bitter civil war in which mujahedeen factions tore the country apart battling for power and killing more than 50,000 people until the Taliban took over in 1996. The militants’ repressive rule lasted until the U.S.-led invasion in 2001. Ever since, the country has been bloodied by insurgency.

“We must understand that there has been suffering on all sides, all Afghans have suffered at different times,” Hamid Karzai, the first democratically elected president after the Taliban’s collapse, said in an interview in Kabul.

“Everyone has done (their) part, unfortunately, in bringing suffering to our people and to our country,” said Karzai, who left office in 2014 after serving two terms. “No one can (point) a finger toward someone to say you’ve done it.”

But individual Afghans can. They know who caused tragedies to their families.

Hayat, one of those visiting the Kabul Center for Memory and Dialogue on a recent day, said the rockets that killed her younger brother and maimed her sister 25 years ago were fired by the men of warlord Abdul Rasul Sayyaf.

Sayyaf was notorious for his ties to al-Qaida in the 1990s and was the inspiration for the Philippine terrorist group, Abu Sayyaf. He is also a powerful politician in post-Taliban Afghanistan, often seen at meetings with Karzai’s successor, President Ashraf Ghani.

Mujahedeen warlords like Sayyaf have remained powerful since the 2001 U.S.-led invasion and head heavily armed factions. They include men like Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who was on the U.S. terrorist list until he signed a 2017 peace pact with Ghani’s government, and Uzbek warlord Marshal Rashid Dostum, who has been implicated in a litany of human rights crimes.

In the immediate aftermath of the Taliban’s 2001 defeat, revenge attacks multiplied, and ethnic Pashtuns, who made up the backbone of the Taliban, were initially harassed and persecuted when they went back to their villages.

As a result, many eventually returned to the mountains or fled to safe havens in neighboring Pakistan. That allowed the Taliban to regroup. Today, the insurgent group is at its strongest since 2001, controlling or holding sway over nearly half of the country.

Even if an intra-Afghan deal is reached, many Afghans fear that the country’s many factions, including the Taliban, will fight for power if U.S. and NATO troops leave.

Under Washington’s deal with the Taliban, U.S. troops are to withdraw by April, 2021, providing that the Taliban honor their promise to fight terrorist groups, most notably the Islamic State affiliate. Trump recently surprised his military by upping the withdrawal date to the end of the year.

“Unfortunately, each time we’ve had a change, someone has tried to take power. It doesn’t work. It hasn’t worked,′ said Karzai. “So let’s learn our lessons and move forward.”

“The day after peace, we must recognize that all Afghans belong to this country … that this Afghanistan belongs to each individual of this country, and that we must live as citizens of this country,” said Karzai. “Only then can we live in a country that looks toward a better future.”

So far, there’s little sign of that happening. Thousands of Taliban prisoners recently released as part of the peace process have already faced revenge attacks, assassinations and abductions, as well as harassment from local officials.

One released prisoner, Muslim Afghan, said he rarely leaves his home in Kabul for fear of retaliation. He doesn’t remember Taliban rule — he was only in the second grade when they were overthrown. But his elders had been senior Taliban members and because of them, the rest of the family was harassed. He said he never joined the Taliban but was arrested in 2014 because of his family connections.

Danish Habibi, who still has nightmares about a Taliban attack, doesn’t know how he can forgive.

“If you are from a family with a victim how will you trust that peace will come, ” he said. He wants victims to sit at the negotiating table — victims of the Taliban, of the mujahedeen, of every side. “They should all have to speak to the victims.”

For Abdullah Abdullah, who heads Afghanistan’s High Council for National Reconciliation, the body tasked with striking a peace deal with the Taliban, negotiating has been an emotional struggle to control his anger at the casualties of the last 19 years.

“I’ve seen too many people suffering, too many casualties on a daily basis, innocent people dying … you cannot hide your emotions,” he said. “But then there is the need of the country. Do we want this to continue forever? There will be endless suffering unless we find a way.”

Associated Press Writer Tameem Akhgar in Kabul contributed to this report.

Copyright 2020 Associated Press. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login