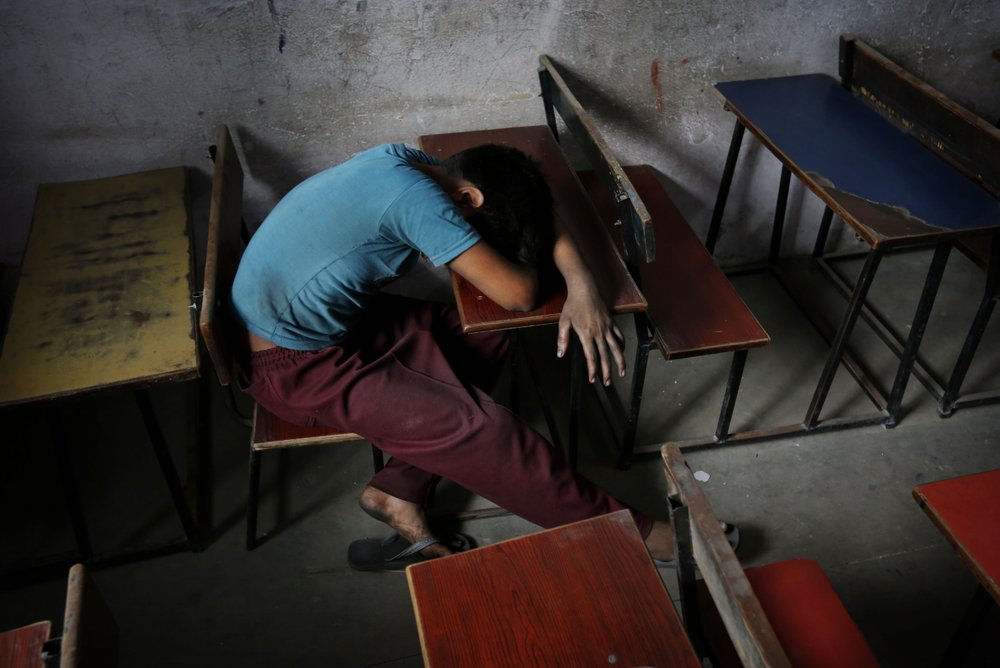

FILE – In this Tuesday, June 11, 2013, file photo, a bonded child laborer rests on a school desk in a safe house after being rescued during a raid by workers from Bachpan Bachao Andolan, or Save Childhood Movement, at a garments factory in New Delhi, India. With classrooms shuttered and parents losing their jobs, many children are working in farms, illegal factories, brick kilns and roadside stalls, reversing decades of progress to stop child labor. In rural India, a nationwide lockdown imposed in March, 2020, pushed millions of people into poverty, encouraging trafficking of children from villages into cities for cheap labor. (AP Photo/Kevin Frayer, File)

LUCKNOW, India (AP) — A boy who cried out when he was beaten for complaining of stomach pains drew attention from a passerby, who alerted police in the central Indian city of Agra.

Officers broke a padlock on the gate of the illegal shoe factory where the boy was working and found a dozen children, aged 10-17.

With classrooms shut and parents losing their jobs in the pandemic, thousands of families are putting their children to work to get by, undoing decades of progress in curbing child labor and threatening the future of a generation of India’s children.

In rural India, a nationwide lockdown imposed in March pushed millions of people into poverty, encouraging trafficking of children from villages into cities for cheap labor. The pandemic is hampering enforcement of anti-child labor laws, with fewer workplace inspections and less vigorous pursuit of human traffickers.

“The situation is unprecedented,” said Dhananjay Tingal, executive director of the Bachpan Bachao Andolan, a children’s rights group whose founder, Kailash Satyarthi, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014.

“These children are made to work 14-16 hours a day and if they refuse to work they are beaten. One beating sends the message down the group, which suits the owner,” said Tingal.

Tingal’s organization has rescued at least 1,197 children between April and September across India. In the same period last year, it helped 613.

Childline, a nationwide helpline for children in distress, received 192,000 distress calls between March and August, most of them related to cases of child labor. It handled 170,000 such calls in the same period of 2019.

The 13-year-old boy who was working in the illegal shoe factory in Agra cannot be identified by name because Indian law forbids naming suspected victims of child labor and trafficking.

He was working 12-14 hours a day attaching the rubber soles of shoes with glue in a small cramped room, with little food and water when police rescued him and other children in September.

He was sent home to Bahraich, a rural town in India’s heartland state of Uttar Pradesh, some 460 kilometers (285 miles) from Agra, with help from the Children’s Welfare Committee, a government body that provides care and protection for children in need.

But with schools closed and his father struggling to feed his four children, the boy went back to work, this time on a farm in his village.

In India, children under 14 are not allowed to work except in family businesses and farms. They are also barred from dangerous workplaces such as construction sites, brick kilns and chemical factories.

The country has made serious gains in combatting child labor, but more than 10 million Indian children are still in some form of servitude, according to UNICEF.

At the height of the pandemic, which has infected more than 9.5 million Indians and killed more than 138,000, the 13-year-old’s father, Sukhai Ram, a landless farmer from the lower end of India’s unforgiving caste system, was jobless and worried.

One day, he met a man who promised to give Ram’s son a job paying about $60 a month. Ultimately, the family only got one month’s pay for the two months the boy worked there before he was rescued.

“I was swayed by those words and allowed him to take my son to the city,” Ram said.

In many cases, families know the child traffickers, said Surya Pratap Mishra, a children’s rights activist.

In some Uttar Pradesh villages, traffickers distributed free food to impoverished families during the pandemic lockdown, which lasted 68 days. Having earned the confidence of the villagers, they offered to give their children jobs in big cities.

“As the villagers knew these people, they agreed and sent their children with them,” said Mishra.

Many did not return for months and were sent home only after being rescued by the authorities and nonprofit groups. Some have not yet been found.

In July, India’s Home Ministry redoubled its fight against the resurgence of child labor, issuing guidelines for urgently setting up Anti Human Trafficking Units in every district. Many Indian states have flouted that advisory.

Ajit Singh, a child rights activist in Uttar Pradesh, said the government’s efforts to protect children since the pandemic began have been abysmal.

Most of India’s elementary and middle schools are still closed because of the pandemic, affecting more than 200 million children. Teachers visit families to check in with students, but online learning is beyond the reach of millions of families that can’t afford smartphones or laptops.

One recent morning in a suburb of the capital, New Delhi, Mohammad Shahzad watched with concern as his 14-year-old son shouldered a heavy bag of sand at a construction site.

“Keep your body stiff. Else it’ll fall,” Shahzad shouted as the boy, a seventh-grader, headed barefoot into the building. At least four other children were working alongside their parents.

With schools closed, the boy will keep working, Shahzad said.

“There is already very little work. If he won’t help us in these trying times, we won’t have enough to eat,” he said.

——

Sheikh Saaliq reported from New Delhi.

Copyright 2020 Associated Press. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login