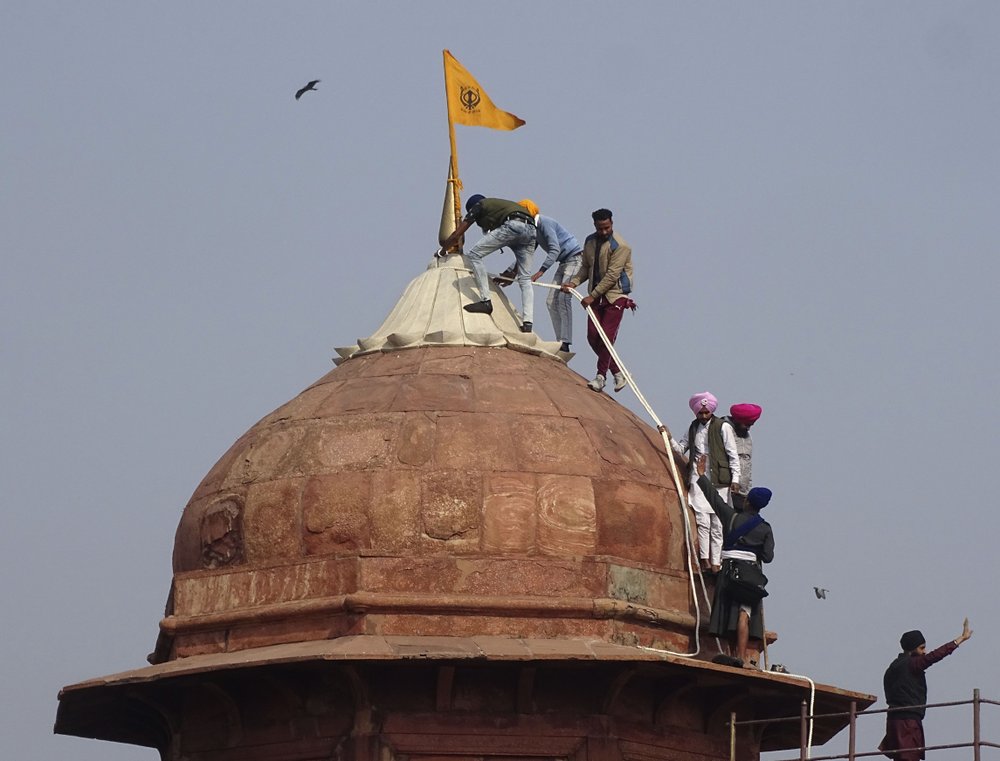

Sikhs hoist a Nishan Sahib, a Sikh religious flag, on a minaret of the historic Red Fort monument in New Delhi, India, Tuesday, Jan. 26, 2021. Tens of thousands of protesting farmers drove long lines of tractors into India’s capital on Tuesday, breaking through police barricades, defying tear gas and storming the historic Red Fort as the nation celebrated Republic Day. (AP Photo/Dinesh Joshi)

NEW DELHI (AP) — Tens of thousands of protesting farmers drove long lines of tractors into India’s capital on Tuesday, breaking through police barricades, defying tear gas and storming the historic Red Fort as the nation celebrated Republic Day.

They waved farm union and religious flags from the ramparts of the fort, where prime ministers annually hoist the national flag to mark the country’s independence.

The deeply symbolic act of taking over the monument, which was built in the 17th century and served as the palace of Mughal emperors, was shown live on hundreds of news channels. People watched in shock at the scope of the farmer protests, now seen as the biggest challenge to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government.

Thousands more farmers marched on foot or rode on horseback while shouting slogans against Modi. At some places, they were showered with flower petals by residents who recorded the unprecedented protest on their phones.

Police said one protester died after his tractor overturned, but farmers said he was shot. Television channels showed several bloodied protesters.

Leaders of the farmers said more than 10,000 tractors joined the protest.

For nearly two months, farmers — many of them Sikhs from Punjab and Haryana states — have camped at the edge of the capital, blockading highways connecting it with the country’s north in a rebellion that has rattled the government. They are demanding the withdrawal of new laws which they say will commercialize agriculture and devastate farmers’ earnings.

“We want to show Modi our strength,” said Satpal Singh, a farmer who drove into the capital on a tractor along with his family of five. “We will not surrender.”

Riot police fired tear gas and water cannons at numerous places to push back the rows upon rows of tractors, which shoved aside concrete and steel barricades. Authorities blocked roads with large trucks and buses in an attempt to stop the farmers from reaching the center of the capital. Thousands, however, managed to reach some important landmarks.

“We will do as we want to. You cannot force your laws on the poor,” said Manjeet Singh, a protesting farmer.

Authorities shut some metro train stations, and mobile internet service was suspended in some parts of the capital, a frequent tactic of the government to thwart protests.

The government insists that the agriculture reform laws passed by Parliament in September will benefit farmers and boost production through private investment.

Farmers tried to march into New Delhi in November but were stopped by police. Since then, unfazed by the winter cold, they have hunkered down at the edge of the city and threatened to besiege it if the farm laws are not repealed.

The government has offered to amend the laws and suspend their implementation for 18 months. But farmers insist they will settle for nothing less than a complete repeal. They plan to march on foot to Parliament on Feb. 1, when the country’s new budget will be presented.

The protests overshadowed Republic Day celebrations, in which Modi oversaw a traditional lavish parade along ceremonial Rajpath boulevard displaying the country’s military power and cultural diversity.

The parade was scaled back because of the coronavirus pandemic. People wore masks and adhered to social distancing as police and military battalions marched along the route displaying their latest equipment.

Republic Day marks the anniversary of the adoption of the country’s constitution on Jan. 26, 1950.

Police said the protesting farmers broke away from the approved protest routes and resorted to “violence and vandalism.”

The group that organized the protest, Samyukt Kisan Morcha, or United Farmers’ Front, blamed the violence on “anti-social elements” who “infiltrated an otherwise peaceful movement.”

Farmers are the latest group to upset Modi’s image of imperturbable dominance in Indian politics.

Since returning to power for a second term, Modi’s government has been rocked by several convulsions. The economy has tanked, social strife has widened, protests have erupted against discriminatory laws and his government has been questioned over its response to the pandemic.

Agriculture supports more than half of the country’s 1.4 billion people. But the economic clout of farmers has diminished over the last three decades. Once producing a third of India’s gross domestic product, farmers now account for only 15% of the country’s $2.9 trillion economy.

More than half of farmers are in debt, with 20,638 killing themselves in 2018 and 2019, according to official records.

The contentious legislation has exacerbated existing resentment from farmers, who have long been seen as the heart and soul of India but often complain of being ignored by the government.

Modi has tried to allay farmers’ fears by mostly dismissing their concerns and has repeatedly accused opposition parties of agitating them by spreading rumors. Some leaders of his party have called the farmers “anti-national,” a label often given to those who criticize Modi or his policies.

Devinder Sharma, an agriculture expert who has spent the last two decades campaigning for income equality for Indian farmers, said they are not only protesting the reforms but also “challenging the entire economic design of the country.”

“The anger that you see is compounded anger,” Sharma said. “Inequality is growing in India and farmers are becoming poorer. Policy planners have failed to realize this and have sucked the income from the bottom to the top. The farmers are only demanding what is their right.”

AP video journalist Rishabh R. Jain contributed to this report.

Copyright 2020 Associated Press. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login