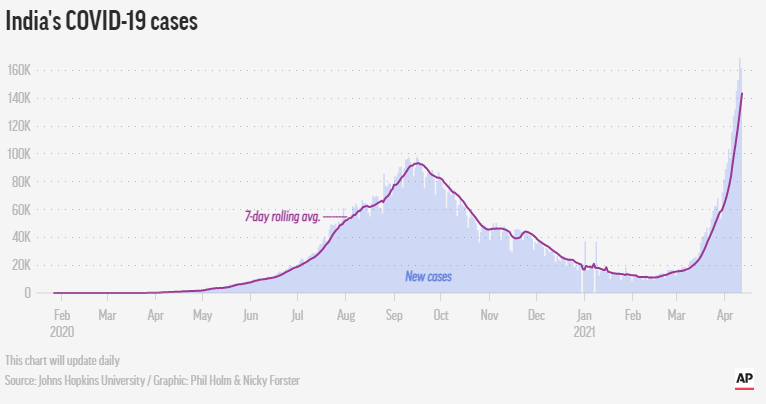

People wait in queues outside the office of the Chemists Association to demand necessary supply of the anti-viral drug Remdesivir, in Pune, India, Thursday, April 8, 2021. India is experiencing its worst pandemic surge, with a seven-day rolling average of more than 130,000 cases per day. Hospitals across the country are starting to get overwhelmed with patients, and experts worry the worst is yet to come. (AP Photo)

NEW DELHI (AP) — The Indian city of Pune is running out of ventilators as gasping coronavirus patients crowd its hospitals. Social media is full of people searching for beds, while relatives throng pharmacies looking for antiviral medicines that hospitals ran out of long ago.

The surge, which can be seen across India, is particularly alarming because the country is a major vaccine producer and a critical supplier to the U.N.-backed COVAX initiative. That program aims to bring shots to some of the world’s poorest countries. Already the rise in cases has forced India to focus on satisfying its domestic demand — and delay deliveries to COVAX and elsewhere, including the United Kingdom and Canada.

India said Tuesday that it would authorize a slew of new vaccines, but experts said that the decision was unlikely to have any immediate impact on supplies available in the country. For now, its focus on domestic needs “means there is very little, if anything, left for COVAX and everybody else,” said Brook Baker, a vaccines expert at Northeastern University.

Pune is India’s hardest-hit city, but other major metropolises are also in crisis, as daily new infections hit record levels, and experts say that missteps stemming from the belief that the pandemic was “over” are coming back to haunt the country.

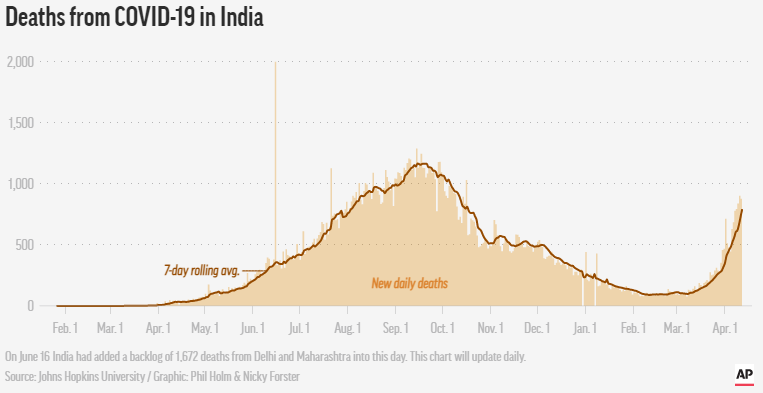

When infections began plummeting in India in September, many concluded the worst had passed. Masks and social distancing were abandoned, while the government gave mixed signals about the level of risk. When cases began rising again in February, authorities were left scrambling.

“Nobody took a long-term view of the pandemic,” said Dr. Vineeta Bal, who studies immune systems at the city’s Indian Institute of Science Education and Research. She noted, for instance, that instead of strengthening existing hospitals, temporary sites were created. In Pune, authorities are resurrecting one of those makeshift facilities, which was crucial to the city’s fight against the virus last year.

India is not alone. Many countries in Europe that saw declines in cases are experiencing new surges, and infection rates have been climbing in every global region, partially driven by new virus variants.

Over the past week, India had averaged more than 143,000 cases per day. It has now reported 13.6 million virus cases since the pandemic began — pushing its toll past Brazil’s and making it second only to the United States’, though both countries have much smaller populations. Deaths are also rising and have crossed the 170,000 mark. Even those figures, experts say, are likely an undercount.

Nearly all states are showing an uptick in infections, and Pune — home to 4 million people — is now left with just 28 unused ventilators Monday night for its more than 110,000 COVID-19 patients.

The country now faces the mammoth challenge of vaccinating millions of people, while also contact-tracing the tens of thousands getting infected every day and keeping the health system from collapsing.

Dilnaz Boga has been in and out of hospitals in recent months to visit a sick relative and witnessed the shift firsthand as cases began to rise. Beds were suddenly unavailable. Nurses warned visitors to be careful. Posters that advised proper mask-wearing sprang up everywhere.

And then, earlier this month, Boga and her 80-year-old mother tested positive. Doctors suggested that her mother be hospitalized, but there weren’t any beds available initially. Both she and her mother are now recovering.

Compounding concerns about rising cases is the fact that the country’s vaccination drive could also be headed for trouble: Several Indian states have reported a shortage of doses even as the federal government has insisted there’s enough in stock.

After a sluggish start, India recently overtook the United States in the number of shots it’s giving every day and is now averaging 3.6 million. But with more than four times the number of people and that later start, it has given at least one dose to around just 7% of its population.

India’s western Maharashtra state, home to Pune and financial capital Mumbai, has recorded nearly half of the country’s new infections in the past week. Some vaccination centers in the state turned away people due to shortages.

At least half a dozen Indian states are reporting similarly low stocks, but Health Minister Harsh Vardhan has called these concerns “deplorable attempts by some state governments to distract attention from their failures.”

Still, India moved Tuesday to expand the number of vaccines available, by authorizing the use of all coronavirus shots that have been given an emergency nod by the World Health Organization or regulators in the United States, Europe, Britain or Japan. Indian regulators also OK’d Russia’s Sputnik V for emergency use.

Worries about vaccine supplies have led to criticism of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, which has exported 64.5 million doses to other nations. Rahul Gandhi, the face of the main opposition Congress party, asked Modi in a letter whether the government’s export strategy was “an effort to garner publicity at the cost of our own citizens.”

Now, India has reversed course. Last month, COVAX said shipments of up to 90 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccines were delayed because the Serum Institute of India decided to prioritize domestic needs.

The institute, which is based in Pune and is the world’s largest vaccine maker, told The Associated Press earlier this month that it could restart exports of the vaccine by June — if new coronavirus infections subside. But a continued surge could result in more delays.

And experts warn that India could be looking at just that.

They suspect the most likely cause behind the widespread surge is the presence of more infectious variants, including a new and potentially troublesome variant that was first detected in India itself.

India needs to vaccinate faster and increase measures aimed at stopping the virus’s spread, said Krishna Udayakumar, founding director of the Duke Global Health Innovation Center at Duke University. “The coming months in India are extremely dangerous,” he said.

Yet, some say the government’s confused messaging have failed to communicate the risk.

Modi has noted the need for people to wear masks, but over the last few weeks, while on the campaign trail, he has delivered speeches in front of tens of thousands of mask-less supporters.

The federal government has also allowed huge gatherings during Hindu festivals like the Kumbh Mela, where millions of devotees daily take a holy dip into the Ganges river. In response to concerns that it could turn into a “superspreader” event, the state’s chief minister, Tirath Singh Rawat, said “the faith in God will overcome the fear of the virus.”

“Optics are so important, and we are completely messing it up,” said Dr. Shahid Jameel, who studies viruses at India’s Ashoka University.

Dozens of cities and towns have imposed partial restrictions and nighttime curfews to try to curb infections, but Modi has ruled out the possibility of another nationwide lockdown. He also rejected calls from states to offer vaccinations to younger people.

Experts, meanwhile, say the current limit of offering vaccine to those over 45 should be relaxed and that shots need to be targeted in areas experiencing surges.

“The burden of COVID-19 is being felt unevenly,” said Udayakumar. “And the response needs to be tailored to local needs.”

___

Associated Press journalists Rafiq Maqbool in Mumbai and Maria Cheng in London contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Copyright 2020 Associated Press. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login