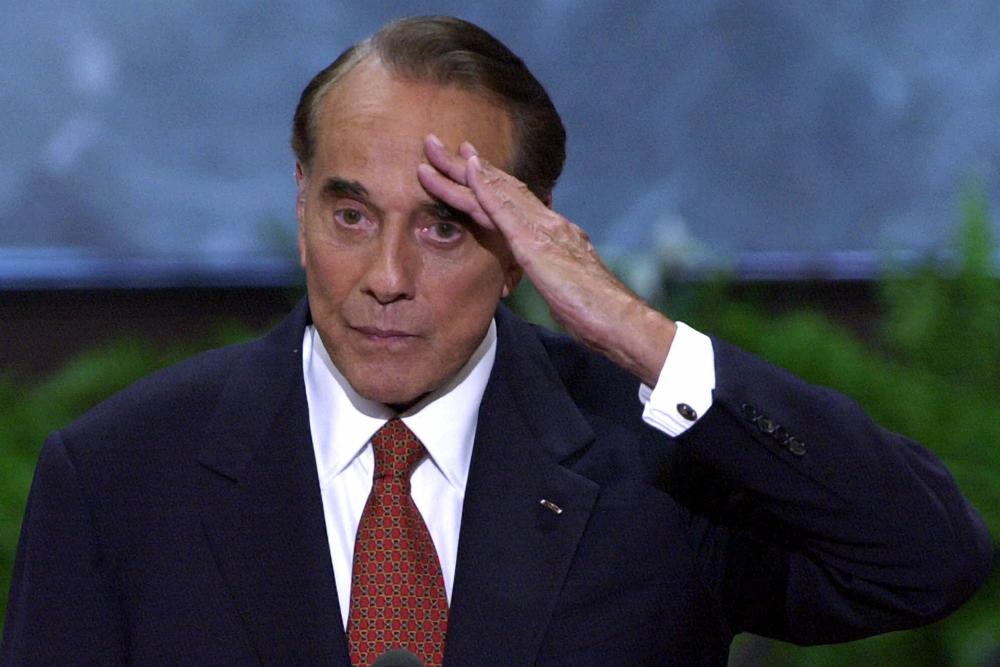

FILE – In this Aug. 1, 2000, file photo, former senator and former presidential candidate Bob Dole salutes after a speech at the Republican National Convention in the First Union Center in Philadelphia. Bob Dole, who overcame disabling war wounds to become a sharp-tongued Senate leader from Kansas, a Republican presidential candidate and then a symbol and celebrant of his dwindling generation of World War II veterans, has died. He was 98. His wife, Elizabeth Dole, posted the announcement Sunday, Dec. 5, 2021, on Twitter. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds, File)

WASHINGTON (AP) — Bob Dole willed himself to walk again after paralyzing war wounds, ran for Congress with a right arm too damaged to shake hands, and rose through the Senate ranks to become a long-serving Republican leader and tough and tireless champion of his party.

He embodied flinty determination to succeed.

Yet Dole, who died Sunday at age 98, was most famous for the times he came up short.

He was the vice presidential running mate in President Gerald Ford’s post-Watergate loss and he sought the presidency himself three times. He came closest in his final race, securing the 1996 Republican nomination only to be steamrolled by President Bill Clinton’s reelection machine.

Dole later said he had come to appreciate the defeats as well as the victories: “They are parts of the same picture — the picture of a full life.”

Representing Kansas in Congress for nearly 36 years, Dole was known on Capitol Hill as a shrewd and pragmatic legislator, trusted to broker compromises across party lines. He wielded tremendous influence on tax policy, farm and nutrition programs, and rights for the disabled.

Colleagues also admired his deadpan wit. Dole wasn’t a big talker; he was most comfortable communicating through a string of zingers and pointed asides.

Those qualities rarely came across on the national political stage, however.

Early on, Democrats dubbed him the GOP’s “hatchet man,” and Dole seemed born to play the part. His voice was gravelly, his face stony, his delivery prairie-flat, even when delivering a quip. He could seem hard-bitten, or bitter, or just plain mean when he lashed out at political opponents.

With each presidential quest Dole tried anew to soften his public persona. He could never pull it off — at least, not until he was out of politics for good.

Just three days after his final race ended in a resounding loss, Dole was cutting up with comedian David Letterman on late-night TV.

Letterman greeted him with a cheeky, “Bob, what have you been doing lately?”

“Apparently not enough,” Dole answered with a grin.

The newly chipper Dole parodied himself on “Saturday Night Live,” wrote two collections of political humor and made a surprising commercial for the anti-impotence drug Viagra, at a time when sexual troubles weren’t so openly discussed.

Dole later said people were always coming up to tell him they would have voted for him in 1996, if only he had been so free and funny in his presidential campaign. But he felt voters preferred gravitas and restraint in their politicians.

“You’ve got to be very careful with humor,” he said. “It’s got to be self-deprecating or it can be terminal, fatal, if you’re out there just slashing away at someone else, and I’ve sort of learned that over the years.”

Out of office, Dole remained dedicated to helping disabled veterans and honoring the fallen. He was a driving force in getting the World War II Memorial built on the National Mall. Into his 90s, Dole still showed up regularly on Saturdays to greet veterans at the memorial.

In September 2017, Congress voted to award Dole its highest expression of appreciation for distinguished contributions to the nation, a Congressional Gold Medal. In 2019, it promoted him from Army captain to colonel.

His announcement in February 2021 that he’d been diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer prompted an outpouring of sympathy, prayers and well-wishes from across the political spectrum. President Joe Biden visited Dole’s home at the storied Watergate complex soon after Dole’s dire diagnosis; the White House said they were close friends.

Dole was born July 22, 1923, in Russell, Kansas, a small farming and oil community. His father managed a cream and egg business and sold bootleg whiskey during Prohibition. The family of six struggled through the Depression and Dust Bowl years. They were so broke they moved into their basement and rented out the rest of the home.

In 1943, Dole, a 6-foot-2 Kansas University basketball player with dreams of becoming a doctor, left for the war.

Army 2nd Lt. Dole was leading an assault against a German machine gun nest in Italy when enemy fire tore through his spine and right arm. He nearly died, and spent three years enduring multiple operations and painful physical therapy.

Dole had to relearn how to walk and bathe and write, this time with an awkward left-hand scrawl.

He never recovered use of his right hand and arm or the feeling in his left thumb and forefinger, making it difficult to button a shirt or cut his meat. Still, Dole earned a law degree from Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas, in 1952.

To avoid embarrassing those trying to shake his right hand, he clutched a pen in it, and reached out with his left.

“I do try harder,” he once said. “If I didn’t I’d be sitting in a rest home, in a rocker, drawing disability.”

That was unquestionably part of his motivation for persuading Congress to enshrine protections against discrimination against disabled people in employment, education and public services.

Today, accessible government offices and national parks, sidewalk ramps and the sign-language interpreters at official local events are just some of the more visible hallmarks of his legacy and that of the fellow lawmakers he rounded up for that civil rights legislation 30 years ago.

Dole became a Kansas legislator and county attorney, won a U.S. House seat in 1960 and moved into the Senate in 1968. His mentor, President Richard Nixon, would send Dole to the Senate floor to assail Vietnam War critics and other senators at odds with the White House.

Nixon rewarded him with a stint as chairman of the Republican National Committee, including the period of the Watergate break-in that destroyed Nixon’s presidency. Dole, cleared of any involvement, liked to quip, “I was off that night.”

He would later size up the disgraced Nixon by branding ex-presidents Jimmy Carter, Ford and Nixon, in turn, “See No Evil, Hear No Evil … and Evil.”

Dole’s aggressiveness won him his first big break in national politics.

Ford chose Dole as a running mate who could fire off verbal attacks while the president kept to the high ground. Dole took on the mission with perhaps too much zeal.

He shocked viewers of the nation’s first-ever vice presidential debate by pronouncing all the wars of the 20th century “Democrat wars” that had killed or wounded enough Americans to populate Detroit.

Dole later said he regretted making a remark that offended so many and didn’t reflect his own views as a veteran. In that campaign, Dole said, “I was supposed to go for the jugular. And I did — my own.”

In the Senate, Dole began to see the value of forging alliances with Democrats, and it became a lifelong habit. He teamed with Democrats to uphold civil rights, expand food stamps, shore up Social Security and create the Martin Luther King Jr. federal holiday as well as to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act.

As Senate Finance Committee chairman, Dole won praise for his handling of a 1982 tax bill that raised revenue to ease the budget deficit. Some fellow Republicans were appalled by higher taxes, however. Rep. Newt Gingrich, R-Ga., called him “the tax collector for the welfare state.”

Dole didn’t think much of Gingrich at the time. “He’s just difficult to work with,” he said. “It’s either Newt’s way or the highway. He’s got a lot of ideas. Some of them are good; not many.”

Nevertheless, Republicans made Dole majority leader in 1984, and he held his party’s top Senate post for more than 11 years, a record until Kentucky’s Mitch McConnell broke it in 2018.

Dole’s 1980 bid for the presidency was short-lived. In the 1988 primaries, he won the Iowa caucuses before losing to George H.W. Bush in New Hampshire, where Dole glared into a TV camera and snapped that Bush should “stop lying about my record.”

Stung by the defeat, he nevertheless used it to poke fun at himself. “The day after New Hampshire, I went home and slept like a baby,” he said. “Every two hours I woke up and cried.”

By the time he finally got his turn in 1996, Dole was 73, making him then the oldest first-time nominee — running against one of the youngest presidents.

Dole tried to turn the 23-year age difference to his advantage, portraying himself as a soldier of the Greatest Generation pitted against an undisciplined baby boomer who avoided serving in Vietnam. But he couldn’t overcome a pronounced charisma gap with Clinton.

Clinton won 31 states, Dole 19.

Dole’s first marriage, to an occupational therapist, Phyllis Holden, whom he met while recovering from war wounds, ended in divorce in 1972. They had one daughter, Robin. In 1975 he married Elizabeth Hanford, a Nixon appointee who later became a senator with her own presidential ambitions. The match endured.

In 2014, asked what he hoped his legacy would be, Dole spoke of hard work for the people of Kansas, and couldn’t resist mixing in a quip.

“That I lived to be 200,” said Dole, then age 91. “Or at least 100. And that I have never forgotten where I was from.”

Cass is a former Associated Press writer. AP writer Jennifer C. Kerr and the late AP writer Tom Raum contributed to this report.

Copyright 2021 Associated Press. All rights reserved.