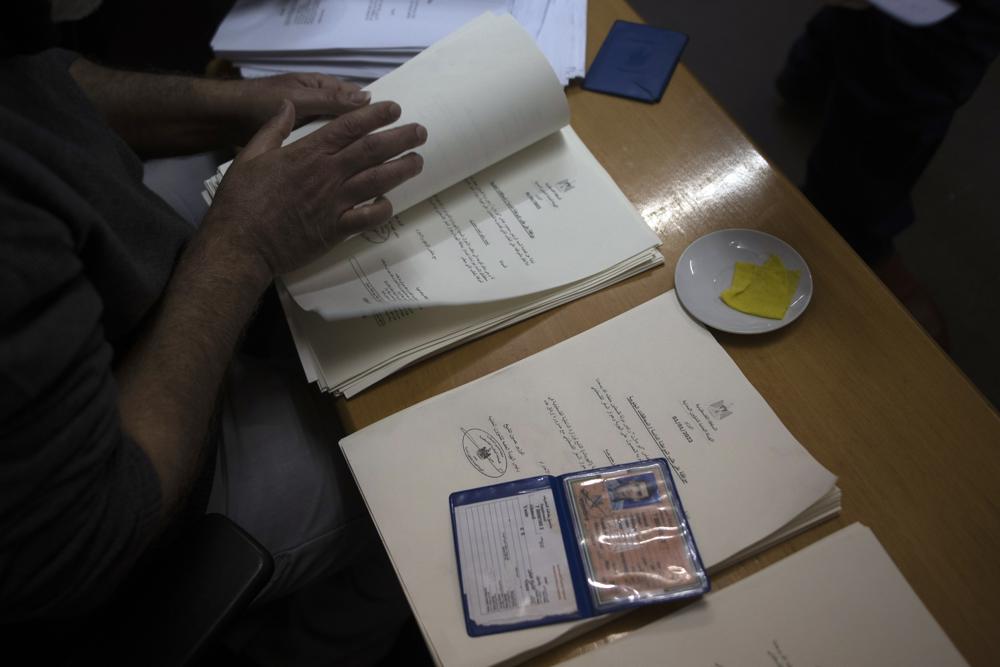

A Palestinian civil affairs employee looks for a name among the letters officially approved by Israel, in his office in Gaza City, Monday, Jan. 3, 2022. In recent months, Israel has approved residency for thousands of Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and Gaza, allowing them to get an official Palestinian ID number that grants them the possibility to travel abroad and clear up years of uncertain legal status. (AP Photo/ Khalil Hamra)

GAZA CITY, Gaza Strip (AP) — Khader al-Najjar has been unable to leave the Gaza Strip since he returned to the Palestinian territory 25 years ago, not even to seek medical treatment for a spinal ailment or to bid farewell to his mother, who died in Jordan last year.

The reason: Israel refused to allow the Palestinian Authority to issue him a national ID. That made it virtually impossible to leave, even before Israel and Egypt imposed a punishing blockade when the Hamas militant group seized control of Gaza in 2007.

In recent months, Israel has approved residency for thousands of Palestinians in the occupied West Bank and Gaza in an attempt to ease tensions while maintaining its decades-long control over the lives of more than 4.5 million Palestinians.

“My suffering was huge,” said al-Najjar, a 62-year-old carpenter, who described a “nightmarish” series of failed attempts to get permits to leave the tiny coastal territory. Now he is among more than 3,200 Palestinians in Gaza who will soon get a national ID.

That will make it easier to travel, but he will still have to navigate a maze of bureaucratic obstacles linked to the blockade. Israel says the restrictions are needed to contain Hamas, while rights groups view the blockade as a form of collective punishment for Gaza’s 2 million Palestinians.

Israel withdrew soldiers and settlers from Gaza in 2005, and Hamas drove out PA forces two years later. But Israel still controls the Palestinian population registry, a computerized database of names and ID numbers. The Palestinians and most of the international community view Gaza as part of the occupied territories.

An estimated tens of thousands of Palestinians do not have legal residency, making it virtually impossible to cross international borders or even the Israeli military checkpoints scattered across the West Bank. Most are people who returned to the territory after living abroad, and Israel refused to place them into the registry.

Ahed Hamada, a senior official in the Hamas-run Interior Ministry, says there are more than 30,000 status-less residents in Gaza alone.

Israel agreed to grant residency to some 13,500 Palestinians in what it presented as a goodwill gesture following recent meetings between Defense Minister Benny Gantz and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. It is the first batch since peace talks broke down more than a decade ago.

Israel’s current government, which consists of parties that support and oppose Palestinian statehood, has ruled out any major initiatives to resolve the conflict but has said it wants to improve living conditions in the territories. It also wants to shore up the increasingly unpopular PA, which governs parts of the West Bank and coordinates security with Israel.

In a statement after meeting with Abbas, Gantz pledged to continue advancing “confidence-building measures in economic and civilian areas.”

Palestinians in Gaza rejoiced and danced as they lined up to receive letters from the PA’s civil affairs authority that will allow them to apply for national IDs and passports. Some shed tears of joy, while others looked on distraught after learning they were not on the list.

Hamas, which has fought four wars with Israel — most recently in May — criticized the Abbas-Gantz meetings, saying they “deviate from the national spirit” of the Palestinian people.

The residency issue dates back to 1967, when Israel seized east Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza in a war with neighboring Arab states. The Palestinians want the three territories to form their future state alongside Israel.

Israel conducted a census three months after the war and only registered Palestinians who were physically present. Israel later allowed some without legal status to visit family on visitor permits. Many Palestinians returned after the Oslo accords in the 1990s and overstayed their permits, hoping their status would be resolved in a final peace agreement that never materialized. Family unifications largely ground to a halt after the outbreak of the second intifada, or Palestinian uprising against Israeli rule, in 2000.

Palestinians are also largely prohibited from moving to the West Bank from Gaza. The latest approvals grant West Bank residency to some 2,800 Palestinians who moved there from Gaza prior to 2007 and who had been at risk of deportation.

Gisha, an Israeli rights group that advocates freedom of movement, says that by presenting the expansion of residency as a goodwill gesture, Israel is merely repackaging something it is obliged to do under international law.

“This is a start, in some ways, but this whole problem has been created by Israel’s stringent policies toward Palestinians under occupation,” said Miriam Marmur, a spokeswoman for Gisha. “There are of course thousands that remain status-less and millions that are still subject to the permit regime.”

Al-Najjar, who lived in Jordan before moving to Gaza, was one of the lucky ones. This month he, his wife and their four children were all granted residency. “Thank God, I can go and visit my sisters and my family (in Jordan) now that we have passports,” he said.

Foreign nationals — mostly Palestinians born in other countries — who have married Palestinians in the territories have found themselves in a similar predicament.

Tareq Hamada said he is still waiting to get residency for his wife, a Palestinian who moved to Gaza from Kuwait in 1997. He said she has dreamed her whole life of making the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca but has been unable to do so.

Fayeq al-Najjar, a distant relative of Khader, tried to return to Gaza from Libya in 2008 but was turned away by Egypt because he did not have a national ID. Instead, he snuck in through the smuggling tunnels on the Egyptian border that have since been largely destroyed. He has applied for an ID but does not know if he will be granted one.

“I have sisters in Egypt who I wish to visit,” he said. “I’m 60 years old, when will I get an ID? When I’m on death’s doorstep?”

Associated Press writers Fares Akram in Hamilton, Canada, and Joseph Krauss in Jerusalem contributed to this report.

Copyright 2021 Associated Press. All rights reserved.