Tricia Cooke, left, and Ethan Coen pose for photographers upon arrival at the premiere of the film ‘Forever Young’ at the 75th international film festival, Cannes, southern France, Sunday, May 22, 2022. (AP Photo/Daniel Cole)

CANNES, France (AP) — Most in the film industry thought Ethan Coen was done with making movies. Ethan did, too.

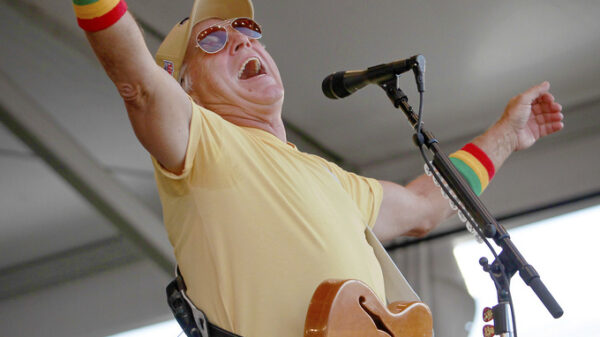

But on Sunday, Coen will premiere his first documentary, “Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind,” at the Cannes Film Festival, a movie that was unknown until last month’s festival lineup announcement. The film, which A24 will distribute later this year, is a blistering portrait of the rock ‘n’ roll and country legend, made almost entirely with archival footage, with riveting extended performances instead of talking heads.

It’s Coen’s first film without his brother Joel, with whom he for three decades formed one of the movies’ most cohesive and unshakable partnerships. But they have lately gone separate ways; last year, Joel made “The Tragedy of Macbeth,” a movie he suggested his brother would never have been interested in. Ethan is now also prepping with his wife, the editor Tricia Cooke (who cut many of the Coens’ films as well as “Trouble in Mind”), a lesbian road-trip sex comedy they wrote together 15 years ago.

“Jerry Lee Lewis: Trouble in Mind” started with their longtime collaborator T-Bone Burnett, who in 2019 recorded a gospel album with the 86-year-old Lewis. The film, as Coen and Cooke noted in an interview ahead of their Cannes premiere, touches on some of the more complicated parts of Lewis’s legacy. (He married his 13-year-old cousin in his early 20s, Lewis’ then third marriage.) But it mostly brings alive the staggering force of the musical dynamo behind “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On,” “Great Balls of Fire” and “Me and Bobby McGee.”

AP: Many thought you, Ethan, were no longer interested in moviemaking. What changed?

COEN: What changed is I started getting bored. I was with Trish in New York at the beginning of the lockdown. So, you know, it was all a little scary and claustrophobic. And T-Bone Burnett, our friend of many years, approached us — actually, more Trish than me — to ask if we wanted to make this movie basically on archival footage. We could do it at home.

COOKE: It was like a home movie project. We’re both huge fans of his music. I had some issues with other parts of Jerry Lee’s life. I was like, “I don’t know if I want to touch that.” But it ended up being a lot of fun. Honestly, T-Bone came to us like two weeks into the pandemic, so it was a life saver.

AP: Ethan, what was it that had sapped your desire to make movies?

COEN: Oh, nothing happened, certainly nothing dramatic. You start out when you’re a kid and you want to make a movie. Everything’s enthusiasm and gung-ho, let’s go make a movie. And the first movie is just loads of fun. And then the second movie is loads of fun, almost as much fun as the first. And after 30 years, not that it’s no fun, but it’s more of a job than it had been. Joel kind of felt the same way but not to the extent that I did. It’s an inevitable by-product of aging. And the last two movies we made, me and Joel together, were really difficult in terms of production. I mean, really difficult. So if you don’t have to do it, you go at a certain point: Why am I doing this?

COOKE: Too many Westerns.

COEN: It was just getting a little old and difficult.

AP: When you say “difficult,” did it have to do with the ecosystem of the industry?

COEN: Not at all, though that’s obviously changed from beyond recognition from where we started at. But, no, it was the production experience and having been doing it for — I don’t know how many years, maybe 35 years. It was the experience of making a movie. More of a grind and less fun.

AP: Has something switched back for you then, since you’re preparing to make a film together this summer?

COEN: Again, it’s all kind of circumstance. We finished this one quite a while ago and we were still sitting around. We had this old script and we thought, “Oh, we should do that. That would be fun.” That’s the movie we’re preparing.

COOKE: I don’t want to speak for Ethan, but I know for myself, at some point, I stopped cutting, pretty much, because my priorities changed. And now our kids are grown and we still get along and have fun making things together. Joel and Ethan, we had written a few of these things, and they were always like, “We’ll put them in a drawer. The kids will find them one day.” Now we’re here like, OK, let’s do that. Let’s open up that drawer and see if someone wants to make this movie.

AP: Do you expect, Ethan, that you and Joel will continue to go your separate ways in moviemaking?

COEN: Oh, I don’t know. Going our own separate ways sounds like it suggests it might be final. But none of this stuff happened definitively. None of the decisions are definitive. We might make another movie. I don’t know what my next movie is going to be after this. The pandemic happened. I turned into a big baby and got bored and quit, and then the pandemic happened. Then other stuff happens and who knows?

AP: Did you always conceive of “Trouble in Mind” as archival-based, no talking heads?

COEN: The movie has a history preceding our involvement. It was originally conceived as being more on the gospel session T-Bone produced with Jerry Lee in 2019. Along the way, they compiled a lot of archival footage. The archival footage kept piling up. It seemed to make more sense to make it about Jerry Lee than this particular session. We pushed it maybe even further that way.

COOKE: When T-Bone brought it to us initially he described what he wanted as a tone poem. I don’t think we did that. (laughs)

COEN: Yeah, that sounds a little fruity.

COOKE: But we did from the beginning not want just a bunch of talking heads, especially if they weren’t Jerry Lee’s.

COEN: T-Bone was explicit about wanting the movie to start with that performance on “The Ed Sullivan Show” of “She Woke Me Up to Say Goodbye.” And he wanted it to finish with “Another Place, Another Time.” And we went “Oh (expletive), that’s great.” He said the whole performances. We said, “Oh, great. So you’re talking about, like, a good movie.”

AP: You each have worked overwhelmingly in fiction film. Had you often pondered making a documentary? Do you watch a lot of docs?

COOKE: I had made a short documentary years ago called “Where the Girls Are” on the Dinah Shore golf tournament. In general, we both love documentaries. Frederick Wiseman and the Maysles and Pennebaker and Barbara Kopple. All of those older documentarians.

COEN: Why are they all old?

COOKE: We’re old.

COEN: Did you see the Beatles documentary? That was fantastic. Goddamn.

AP: The more distance we get from the films and music of mid-century America, the more it seems to me that was such a fertile period of creation that will never be repeated. Like: Wherever Jerry Lee Lewis came from is not a place anyone comes from anymore.

COEN: I totally agree. It’s like, yeah, it’s all gone now.

COOKE: Things aren’t discovered the same way. For Jerry Lee, when he was young, going to a blues club was nothing he had access to before and it became this incredible passion. Everything now is so large, so global — not that that’s necessarily a bad thing — but it doesn’t feel like it has the same passion as it did in the ’30s, ’40s, ’50s.

AP: When you see him performing, his arms going up and down like pistons, he’s such a dynamo that you can’t help wondering where that energy came from.

COEN: Musicians are freaks. I mean it in the best possible way.

COOKE: He talks about the Pentecostal Church. It’s almost like he’s overcome with this passion for playing. I just remember being mesmerized when we first started watching the footage.

COEN: Sifting through the archival footage was a once-in-a-lifetime blessing but also a curse. Because he did his share of (expletive) stuff, too.

AP: What’s your personal thresholds in the behavior of an artist and the art they make? “Trouble in Mind” pointedly doesn’t seek to cast judgment.

COEN: If it’s a good movie, that’s why it’s good. What are we supposed to make of that? Right. That’s a permitted question. That’s what makes the movie interesting. How do you put that magnetic performer together with that flawed person? It’s kind of like — I mean none of the Beatles married their 13-year-old cousin — but it’s kind of like the Beatles movie and why it’s so thrilling. You go: Wow. These are both huge cultural figures and smaller-than-life human beings. That’s what’s mind blowing.

Jerry Lee is much the same. I don’t think any sane person is going to ask to embargo the music because his character had certain flaws. Who imposes that choice? All glory to T-Bone for presenting us with the opportunity and saying that it’s going to be about Jerry Lee, about this musician, and it’s not going to be about talking heads telling us what to think about Jerry Lee or about us editorializing, telling the audience what to think about Jerry Lee. All of those things are not recipes for making a good movie and no service to Jerry.

Copyright 2021 Associated Press. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login